This is the second in a series of five blog reposts

By the summer of 2005, I had been writing what was to become Loon for nearly three years. It had been transformed from a compendium of 100 letters home into an almost-book with half as many letters and a correspondingly increasing amount of prose. I received positive feedback from friends, family, and even Washington DC military insiders.

During that period, an incredible situation unfolded. Day by day, large thanks to the burgeoning internet, my former Vietnam buddies emerged from the woodwork. With them came floods of memories. We began to regularly get together, first in twos and threes then, over time, in greater numbers.

"Do you remember those three days in June 1968? Did that really happen?"

We listened to each other and cried, laughed, and argued.

"No, no, you shithead, that's not the way I remember it. Here's how it really happened..."

As each former comrade-in-arms emerged, the tears, the laughs, and the arguments continued anew. But over time the stories became clearer - even lucid. We gained access to unseen unit diaries, found actual rosters of the wounded, and poured over the names of the dead.

Oh, so many dead.

As I shared my letters with the new arrivals, I realized that I had created a record of our time in Vietnam. Few of the boys wrote letters home with content relevant to our actual activities. More often than not, this was intentional so as not to upset their families.

The letters found their way to the mother of one of our boys. She wrote to emotionally tell me that this was her first knowledge of the details of her son's life in Vietnam. That blew me away and reinforced my determination to keep writing, despite having neither a job nor a clue as to how such a book might become published.

I'd already been well introduced to one agent and, after a year of trying, struck out. I'd spent months working with a major military publisher and struck out again. But for the reinforcement of family, friends, and fellow Marines, I'm certain I could not have gone forward.

Seeing my discouragement during a down moment, a marine buddy laid it out.

"Listen to me Jack, this ain't just your story, this is our story. It belongs to all of Charlie Company and it must be told. You can write it. We can't. Get it? Now get off your ass and get this thing done."

I wonder if my writing career might have launched earlier had my mother ever given me such an admonition.

So, I kept writing and I kept networking. I wrote to publishers, agents, and authors. Most were around Washington where I was living at the time, but I also made several trips to New York. Soon I realized that it was important to have an agent and really important that she have a 212 area code.

My break came early in 2007.

Friends arranged a breakfast for me to meet a local newspaper reporter who was not only a former marine, but also the author of a well received book about the Vietnam era. I subsequently sent him excerpts of my writing which he then offered to share with his agent in New York.

Wow!

It still took nearly a year for me to wangle an appointment with the agent and even then she offered little encouragement. That being said, however, there I was on Bleaker Street in Greenwich Village talking with the head of one of New York's legendary literary agencies. We parted after 20 minutes. She asked that I send her the manuscript. She'd take a look when she had time.

No airplane was required for my return flight home to Washington.

Weeks passed. Months passed. No word.

My phone finally rang in early April. I was in Thailand attending my daughter's wedding.

"Jack? Have you considered retaining an editor? It may cost you."

An editor?

"Can you suggest someone?"

"Yes, I have someone in mind."

The editor suggested was a freelancer who had worked for Random House, had solid experience with war writing, was willing to take a look at the manuscript, and understood the big idea. Loon had evolved from a series of letters into a book about America in the mid 1960's. I was left to wonder how it was that my cell phone worked in Thailand.

And, the times were changing. As the population aged, there was increasing interest both the Vietnam War and America in the late 1960's. After five long years, it appeared that I might be in the right place at the right time.

The book needed help to get the interest of a major publisher. I was on the road.

It would take two more years to bring Loon to market, but in April 2007, I knew we had crossed the Rubicon.

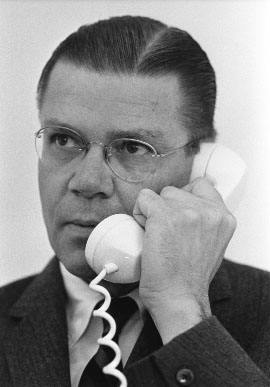

AKA Robert Strange McNamara

AKA Robert Strange McNamara